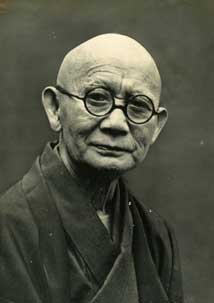

Northwest of central Tokyo lies the city of Niiza in the Musashino area of the Kanto plain. Here, you can find Heirinji temple, a Buddhist temple of the Rinzai tradition. The temple grounds enclose a preserved section of Musashino’s indigenous forest, which has since been declared a national treasure. On the far left as you enter Heirinji temple is the hansobo (a small shrine contained within the temple grounds). The hansobo was occupied by Ogura Tetsuju, Yamaoka Tesshu’s last and most senior disciple. Ogura was 52 years old, and was planning to live out the remainder of his life there in ascetic retreat, as is customary for the lifetime student of Rinzai Zen. The year was 1918.

Also present at Heirinji for training in Zen was Mitamura Engyo, the noted scholar of Edo-period literature. Both Ogura and Mitamura came to Heirinji as disciples of Daikyuu roshi, the former head of Myoshinji Temple in Kyoto. Mitamura was a long-time practitioner of misogi (Shinto ascetic / purification practices). At Mitamura’s encouragement Ogura began training with the Misogi-kyo religious sect in addition to his practice in Zen. At the time, Misogi-kyo was headquartered in Ushigomekawada-cho, but moved to Nakano Ward (near present-day JR Nakano Station) a couple of years after. When people hear the word “misogi,” they often picture standing under icy waterfalls with palms pressed together. Misogi-kyo was not like this at all. The training consisted of loudly chanting, or shouting, the single line: “TO HO KA MI E MI TA ME” over and over again. It was similar to some kinds of Buddhist chanting, which often involve a single line or text repeated indefinitely.

It is possible that this practice, this exhaustive, furious shouting, reminded Ogura of Tesshu sensei’s younger days when the kiai rang out from the dojo (Tesshu sensei’s Shunpukan) through hour upon hour of intense training. Ogura spent much of his time training young people. If he were alive today, he would probably think this training the best thing to toughen up today’s pampered youth.

At the time, there were some young practitioners of Zen at Heirinji Temple; a group of students from Tokyo Imperial University (later renamed Tokyo University). They walked 25 kilometers — a full day’s travel — to meditate at the temple. Ryokichi Nagai Was one of these young men.

When the students had time, they liked to go to the hansobo and talk with Ogura, and he seemed to enjoy their

company as well. One day, Mitamura and Ogura came to the students with a challenge. “Where is this ever going to get you, just sitting there like a bunch of cowflops? How about something a little more appropriate for young men like yourselves; training that will exhaust you, body and soul!” Agreeing to try this “new training,” Nagai and the other students took their first step toward founding the Ichikukai Dojo.

Nagai was on the Engineering Department rowing team at Tokyo University. The Engineering Department had never won any of the interdepartmental races. After his first experience with misogi, Nagai enthusiastically recruited the other members of his team. As if by design, the Engineering Department team won the Tokyo University races that very year. Universities in the area heard of the small team’s rapid improvement, and soon rowing teams from all over Tokyo came to do the training, lest they fall behind.

At that time, the students began meeting once a month to practice misogi with an existing misogi-kyo group. Ogura acted as instructor to the students, and decided that they should meet on the 19th of each month. The name “Ichikukai,” is derived from this; it literally means “one-nine group.”

Rowing, as a sport, tends to draw big, strong men, so soon enough crews of strapping college students began filing into regular misogi-kyo practice. The youths’ wild enthusiasm as well as their sometimes frighteningly severe discipline intimidated and disturbed the more sedate senior practitioners. Before long, people opposed to the students’ presence made their feelings known.

The year was 1922. Nagai and some of his older Tokyo University classmates decided it was time to make a place of their own, where they could “practice however they pleased, without worrying about offending anyone.” Tokyo University students formed the foundation of the drive to put this plan into action. To clarify their intentions, the students wrote a treatise, entitled “Toward the Building of a New Dojo (training hall).” The treatise provides a snapshot of the time; it encapsulates the passion and purity of spirit that these young men held in their hearts at the time. It runs a bit long, but it is well worth reprinting here in full:

Toward the Building of a New Dojo

Our practice of misogi shugyo is the desperate, ravenous, fierce and relentless seeking of truth and purity. In order to bring forth and strengthen that core most essential to humanity, we break our bones in training. This training is a way to devote body and soul to that quest.

Today’s world is a mess of mixed-up ideas, and young people feel lost. While misogi shugyo does not necessarily solve the problem completely, we believe it does offer a way out of the confusion. Materialistic and emotional concerns have become convoluted and strange, leaving a world populated by masks and empty husks. Many people still huddle behind those masks; alone, afraid, and without hope.

Misogi shugyo is about exploding this dualistic life, and distilling from it the true, genuine and natural state. There is nothing for us now but to strip ourselves naked to the bone, jump in boldly with both feet, and see with our bare eyes what lies at the ground of our being.

We have already formed an organization called the Ichikukai. We eat only rice mixed with barley, a few slices of takuan (pickled daikon radish) and a bit of miso (fermented bean paste). We live together a few days per month, eating this simple diet, chanting the misogi-harai-kotoba TO HO KA MI EH MI TA ME as loud as the strength in our bodies permits, until we dissolve in the essence of the practice itself.

When the training has ended, participants often feel deeply shaken or moved, sometimes to tears and embraces. We feel the wellspring of truth directly, and it is overwhelming.

We are now planning to build a dojo for the purpose of continuing training. We are aware that as students, we have very little in the way of financial resources. We are also aware, however, that if we focus all our efforts on achieving this goal, nothing can stop us. Fellow students! Join us in this journey.

In May of 1923, in Tokyo’s Nokata-mura, the first Ichikukai Dojo was constructed on a plot of land roughly 1650 sq. m in size. Although it is commonly said that the students built the first dojo, the truth is the funding mostly came from their relatives.

Hino sensei and his wife

The students did handle as much of the work as they could, their passion drawing supporters from the woodwork. When Ogura Tetsuju sensei was persuaded to depart from Heirinji Temple and join the students at the Ichikukai, the dojo as we know it today was born.

Thus 1923 became the first year of Ichikukai history. It was Tetsuju sensei’s wish that the training be through Zen and Misogi in tandem. At the time, Zen practice was held under the guidance of Daikyu roshi (Zen master). For reasons that are unclear, the roshi stopped leading Zen practice. Tetsuju sensei (thereafter followed by Ishizu Mutoku sensei and Hino Tesso sensei) re-started and began leading Zen practice in 1928.

The first roshi to officially preside over Zen practice at the Ichikukai ended up being Maigan roshi. Once the head abbot of Kamakura’s Engakuji Temple as well as Kyoto’s Daitokuji, he died shortly after the war. He was an extremely severe roshi, and his sesshin-kai (concentrated meditation seminars) were intense.

After Maigan roshi’s death, Heirinji was led by Keizan roshi, who led the sesshin-kai at Ichikukai for thirty years. He was in turn succeeded by Nonomura Genryo roshi, who carries the line to this day.

Tetsuju sensei’s students built a tea hut inside the area of Jochiji temple in Kitakamakura, named it Tetsuju-an and gave it to him as a gift to celebrate his 70th birthday. From that day forward, he left the dojo at Nakano entirely in the hands of Hino sensei and his wife, and he moved into the hut. On April 1, 1944, Ogura sensei passed away and buried on the grounds of Jochiji Temple.

By that time, the Ichikukai had quite a few members, and in 1938 the decision was made to change the dojo’s status; by 1939 it was declared a Social Service Institution.

The grounds at the Nakano dojo were beginning to feeling a little small. Partially due to the noise produced during shugyo and the closeness of residences in the neighborhood, preparations were made for a move. In 1963, a plot of land (2300 sq. m) was purchased at the dojo’s current location (3-4-10 Maesawa, Higashi Kurume-shi, Tokyo). The next year a modern ferroconcrete dojo was built on this site. The dojo has two floors; the first floor is for misogi, the top floor for zen. The original dojo at Nakano was full of memories for many, built by the sweat and stained by the blood of Ichikukai members from years past. As such, the building was moved part and parcel to the new location. It stands there and remains functional to this day.

Again the Ichikukai grew, and many members sought a deeper level of training. In this way, people realized that it is through religion and religious traditions that this practice is possible. As this sentiment mede itself known, the decision was made to change from a “Social Service Organization” to a proper “Religious Organization” as designated by the government.

While the appearance of the dojo has changed from a humble house that doubled as a dojo to a looming concrete building, the spirit of the place is the same as it was in Ogura sensei’s time. It is a tough, “old style dojo” whose life and every breath are shugyo itself.

To that end, to keep the practice in its most pure form, the small fee accepted from zen or misogi practitioners is used exclusively to keep the dojo running. Neither the head of the dojo nor the board members receive anything in the way of pay or compensation. In this way, the dojo has been able to stay afloat in the wake of the Great Kanto Earthquake and other times of strife. Through all this we have continued to launch promising people into all echelons of society.